There are three events in Quebec’s history that have marked our

collective consciousness as a nation more than any others: the Conquest of 1760; the Annexation of Lower

Canada in 1840 following the defeat of the Patriotes in

1837-38 and the passage of the Act of Union by the Westminster Parliament in

1840, which combined Upper and Lower Canada into a united Province with a

single legislature; and, finally, the Constitutional reform of 1982 to the

exclusion of Quebec.

These, we may say, represent three major “defeats”

in the history of a people whose name gradually changed from Canadiens to Canadiens français and most recently to Québécois.

Moreover, these three defeats are defining events in our history — our

political history of course but, clearly with regard to 1760 and 1840, in other

dimensions as well: economic, social, and cultural. Today, the quest for the

survival of a French identity in a majority English-speaking country and

continent remains central to Quebecers’ identity and a reality inseparable from

the Conquest.

The first major defeat: 1759

After 1760, Canadiens not only lost their commercial empire in the

West but most of their access to executive positions, to the detriment of

individual socio-economic success and the capacity to shape their destiny as a

people. Before 1760, Canadiens had access to most of the most important

business, military, and political positions in the colony, as illustrated

(toward the end of the regime) by Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil (1698-1778), the

last governor general of New France, a Canadien born and raised in Canada.

After the Conquest, not only did the population

lose some of their elites, who moved on to pursue their careers elsewhere in

the French Empire, but those who remained in New France lost their handle on

government, administration, big business, and the military. The Canadien gentry

entered into decline. Gradually, the colony’s elites were overwhelmingly

composed of the WASP minority, power residing in the hands of London and of men

nominated by Britain. Later that overarching power shifted to Ottawa, an almost

entirely English-speaking government before the 1970s, and one that from

Quebec’s perspective remains today the expression of an English-Canadian

majority, even if at times with strong Quebec contingents.

If the upper class and executive levels of Quebec

society were, for the most part, inaccessible to French Canadians, the Quebec

Act of 1774, resolving the status of French civil law and setting up a

legislature, did leave a space for a French Canadian middle class to

consolidate its position and eventually to lead a movement contesting

inequalities in the colony, especially using the Legislature founded with the

Constitutional Act of 1791 (for which some members of this class had petitioned

in the 1780s). So much so that, having become overly optimistic, the leaders of

what was first called the Parti

canadien, later termed Parti patriote and

led by Papineau, were for decades confident that self-determination would be

obtained gradually without great difficulty, and at first within the Empire.

They saw this as the natural course. If the American and French Revolutions

were more radical, they believed Britain, with its liberal constitution, simply

espoused the same ideals with a more moderate approach, and thus would accept

the gradual and friendly emancipation of its colonies. They believed long

before that they could obtain for Lower Canada the same things that in time the

English-Canadian majority achieved for the Dominion in 1867.

Indeed, the North American colonial context had

proven favourable toward alleviating the oppression of French Canadians. The

legal exclusion of Catholics in 1763 with the Proclamation Act was reversed in

1774 with the Quebec Act. In 1791 the Constitutional Act went

one step further with the creation of a Legislature to which the colony’s

Catholics could be elected. Monsignor Plessis, in 1799, thanked Providence that

the Conquest had saved Canada — French Canada — from the French Revolution (as

well as the American one).

The leaders of the Catholic Church were not the

only ones to develop a positive outlook on the Conquest or on British rule.

Even though the constitution of 1791 was gained at the expense of the loss of

considerable fertile land to Upper Canada, the Canadiens’

new political leaders, after 1791, were generally optimistic. They believed

British imperial policy would evolve positively, that democracy and

self-determination, through gradual autonomy, were achievable for Lower Canada.

London could even be an ally, they believed, against the more rabid

representatives of British imperialism within the colony, hardline elements

that had clashed with governors Murray and Carleton in the early days of the

British regime. This proved to be wrong: the emancipation of Lower Canada

garnered a strong and vehement opposition from British colonists. Lower

Canadian independence, they argued, was not in Britain’s interest. Lord Durham

would state this explicitly in his report in 1839, proposing a plan that

would ensure French-speakers were a minority in a merged province. Based on his

report, the Union Act of 1840 placed the French in a minority.

What had brought about Durham’s report and the

Union Act? In the 1830s, after decades of political struggle with few

substantial gains, the dominant leaders of the Patriote party,

following Papineau, had begun to lose confidence in the peaceful path to

democracy and self-determination. Increasingly, they believed London had to be

challenged — especially given that the Governor’s powers remained little

changed since 1791, while the colonization of new lands was being monopolized

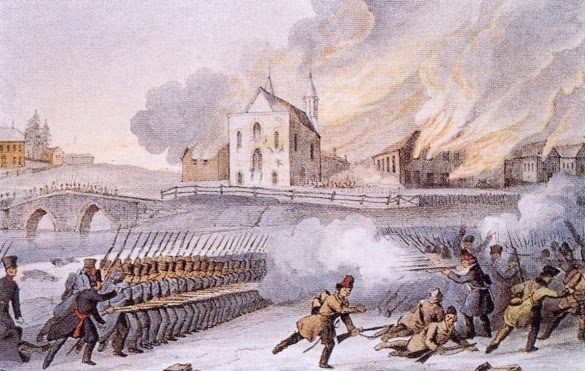

by the government to the exclusion of the Canadiens. The firm rebuttal they received in 1837 with the

Russell Resolutions and the violent repression that ensued in the Rebellions of

1837-38 under General Colbourne, put an abrupt end to naive optimism. Canadiens would

no longer envisage their independence as part of an easy and gradual evolution,

in the natural course of things. As an immediate consequence of the failure of

the Patriotes to overthrow British rule in 1837-38, Lower

Canada was subordinated to the United Province.

Ever since the Union Act, which took effect in

1841, Quebec has remained part of a larger jurisdiction in which the

English-speaking element is a majority — in fact a majority that has increased

along the way. This is largely due to the rapid pace of population growth

through immigration when new Canadians integrate, culturally, to the

English-Canadian majority in much greater numbers than to Quebec’s francophone

majority.

For decades, most French Canadian leaders would

either partake in pan-Canadian politics, adapting to the English majority’s

vehicles, the federal Liberal or Conservative parties, or reverting to cultural

nationalism and resistance to assimilation. The latter, the nationalists,

attempted to find long-term solutions to their economic exclusion that came to

fruition in the 1960s and 1970s.

The ‘second conquest’: 1840

The renewed “conquest” of 1840 was a defining event

in Quebec history. It sealed, for more than a century, the destiny of the

French-speaking nation, reducing it to minority status in a manner that shaped

its national consciousness. French Canadians henceforth conceived of themselves

as a national minority, developing complexes about disadvantages and the

economic and political leadership set over them, to the extent that they became

afraid to make claims for themselves. The governing elite pronounced them to be

inferior, and French Canadians adapted to a world in which their exclusion from

certain circles and executive positions was almost a given, to the point of

interiorizing some of these complexes. This inferiority complex had not yet

crystallized before the failure of the Rebellions and the ensuing annexation of

1840, which may therefore be regarded as a turning point.

It might seem surprising, but confederation only

furthered the sense of inferiority because even though a provincial “nation

state” of Quebec was reinstated in 1867 with a capital and legislature at Quebec

City, French Canadians continued to participate in its governance as if they

were a “minority” in a British-dominated province. This is best illustrated by

the fact that their political formations, Liberal and Conservative, were in

every way incorporated and subordinate to the federal, Canada-wide party

structures. In a province with 75% or 80% Catholic francophones since 1867,

finance ministers were usually anglophone and Protestant, up to Maurice

Duplessis’s return to power in 1944.

The only real exception before the advent of the

Union Nationale movement was Honoré Mercier’s parti national coalition after

the hanging of Riel in 1885. Mercier was elected in 1886 but the passing of the

reins of power was delayed by the lieutenant-governor, who toppled the newly

re-elected government in 1891. Indeed, Mercier’s government, which actively

pursued national assertion and provincial autonomy, had already met with

serious federal opposition. Apart from Mercier, most Quebec politicians did not

rock the boat. After all, economic power still eluded the majority of

Quebecers.

Instead, nationalism found expression mainly in

intellectual movements such as those founded by admirers of Henri Bourassa in

the early twentieth century or in the influential network of movements around

the priest-historian Fr. Lionel Groulx. His latter movement found a political

expression in the Action Libérale

Nationale whose reformist programme was popular

in the 1935 and 1936 Quebec elections. They wanted to overthrow the “colonial

order” in Quebec and make French Canadians “masters in our own house” through

provincial legislation, such as by nationalizing hydro-electricity. Their

alliance with Duplessis conservatives, though, which bore fruit in the Union

Nationale under his leadership, resulted in the abandonment of all the more

radical changes proposed in their programme after the 1936 election victory, in

favour of a more restrained defense of provincial autonomy.

It is only with the Quiet Revolution that

governments renewed a more aggressive programme, including the nationalization

of hydro in 1962. This new dawn launched a fast-paced “emancipation” movement

that had been advancing slowly, almost subterraneously, in the preceding

decades, but which had for the most part been stalled or sidelined politically

since confederation.

Where was all this leading? The provincial Liberals

under Jean Lesage and the more conservative Union Nationale under Daniel

Johnson both believed that not only were they competing for a “national”

government, but that Quebec’s status required a wide-ranging modification of

the Canadian constitutional order which Johnson summarized in the slogan

“Equality or Independence.”

In its own way, René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois,

established in 1968 and advocating “sovereignty-association,” proposed another

version of this remodelling of the constitutional order. Short of outright

independence, they seemed to espouse a form of national self-determination of

Quebecers without breaking altogether from Canada, much like the status

gradually achieved by the Dominion of Canada within the British Empire.

A third ‘defeat’: 1980-82

At first, there even seemed to be openness to this

in Ottawa. It is not impossible to imagine negotiations between Daniel Johnson

and Robert Stanfield had they held power simultaneously in Quebec City and

Ottawa — in contrast to the brick wall presented by Pierre Trudeau. For a brief

moment, Quebec appeared to be confidently on the path toward freeing itself

from two hundred years of subordination.

Instead Trudeau, ensconced as Prime Minister,

emerged as the herald of those who staunchly opposed devolution. French

Canadians voted both for Trudeau and Lévesque, seeming to believe that both

could be their champions. Trudeau promised a “renewed” Canada. Rather than a

negotiated association between two nations, he advocated one Canada, bilingual

and multicultural, that would break away from its two national traditions

(British and French) in favour of a new identity.

The advent of Trudeau would lead Ottawa and Quebec

City to clash, and Ottawa to enter into a long-lasting organizational mould of

blocking as far as possible any devolution while at the same time always

expanding the role of the federal government. Faced with the opposition of a

French Canadian Prime Minister opposed to negotiation, and aptly pushing all

the buttons of Quebec’s inferiority complexes since 1837, Lévesque’s strategy

failed in the 1980 referendum. The prerequisite of Lévesque’s strategy was

reciprocal English-Canadian goodwill, open to negotiation, which meant that the

1980 referendum was doomed to fail once Trudeau returned to power.

This sealed the defeat of national affirmation,

with Trudeau imposing a new constitution on Quebec that saw his vision triumph:

bilingual (for individuals and services, but not truly bicultural or

binational), multicultural, and centered on the federal government. In

practice, this new constitution has been made very difficult to reform, blocked

first by Trudeauists’ influence on public opinion during the Meech Lake fiasco,

then by various laws limiting the possibility of constitutional reform under

Chrétien, according to principles of regional veto that hadn’t been respected

in 1981-82.

Quebec now seems stuck, half-in, half-out in

national terms, without any clear view of feasible solutions to this renewed

subordination in an order that it does not really accept. As was the case after

1840, Quebecers seem resigned to having to evolve as an unwilling national

minority. The persistence of a sovereigntist or separatist movement in Quebec

leaves open the possibility of new movements in the future — but at present

Quebecers seem not only divided but very hesitant as to what path to follow.

Perhaps what is most striking though, in 2012, more

than the election of the PQ with a small plurality of seats, is the overly

aggressive reaction to the Quebec campaign and the PQ’s nationalist programme

in much of the English-speaking media. Measures that are commonplace in many

Western democracies are suddenly presented in serious editorials as the most

viciously racist policies in the West. This surely is an indication that old

colonial complexes and relationships between English and French Canada linger on.

In the 1950s, historian Maurice Séguin used to say

that French Canada (or Quebec) was too strong to assimilate, but too feeble to

break away. In the 1960s and 1970s, with the Quiet Revolution, increasing

numbers of Quebecers — and even foreigners, notably De Gaulle of France —

believed this to be no longer the case. Most strikingly, René Lévesque himself,

in his 1967-68 essay Option Québec, claimed that sovereignty would be achieved easily

and soon, as a natural process. The rise to power of Trudeau proved him wrong

and, since the imposition of a new constitutional order in 1982, together with

two referendum defeats and the electoral collapse of the Bloc Quebecois,

Séguin’s conclusion would seem to enjoy a renewed resonance.

An excerpt from Three Conquests of Quebec by Charles-Philippe Courtois published in the Dorchester Review December 20, 2012

No comments:

Post a Comment